Don't Migrate, Harmonize: A Practical Setup for Claude + Codex Skills

Over the last few weeks, I have found myself switching between Claude Code and Codex. With Claude Code, it’s great fun to start a project. When you go deeper into the trenches, Codex has the sharper axe. It’s much slower than Claude Code, but often the first solution from Codex just works, even when Claude Code has tried a few times already.

Also I wanted to try out these lines from a Go expert for my AGENTS.md file on both agents. Especially the part with no longer leaving behind build artifacts would be much appreciated.

I found some information about migrating skills and other central files from the cloud to Codex, but I couldn’t find a good way to harmonise them. The following is the result of a coding session. It’s a description of the architecture I ended up with and the small set of rules that make it work.

Please note that my skills usually consist of an Markdown file and a bash script. The Markdown file establishes the correct parameters to send to the script. These depend heavily on the environment we’re running on and what we actually want to do. I also found it to be a much nicer interface than having to come up with parameters myself on the CLI. I also make the agents responsible for supervising the script and checking that the output is as intended. This is also helpful for me and much faster than I could do it myself.

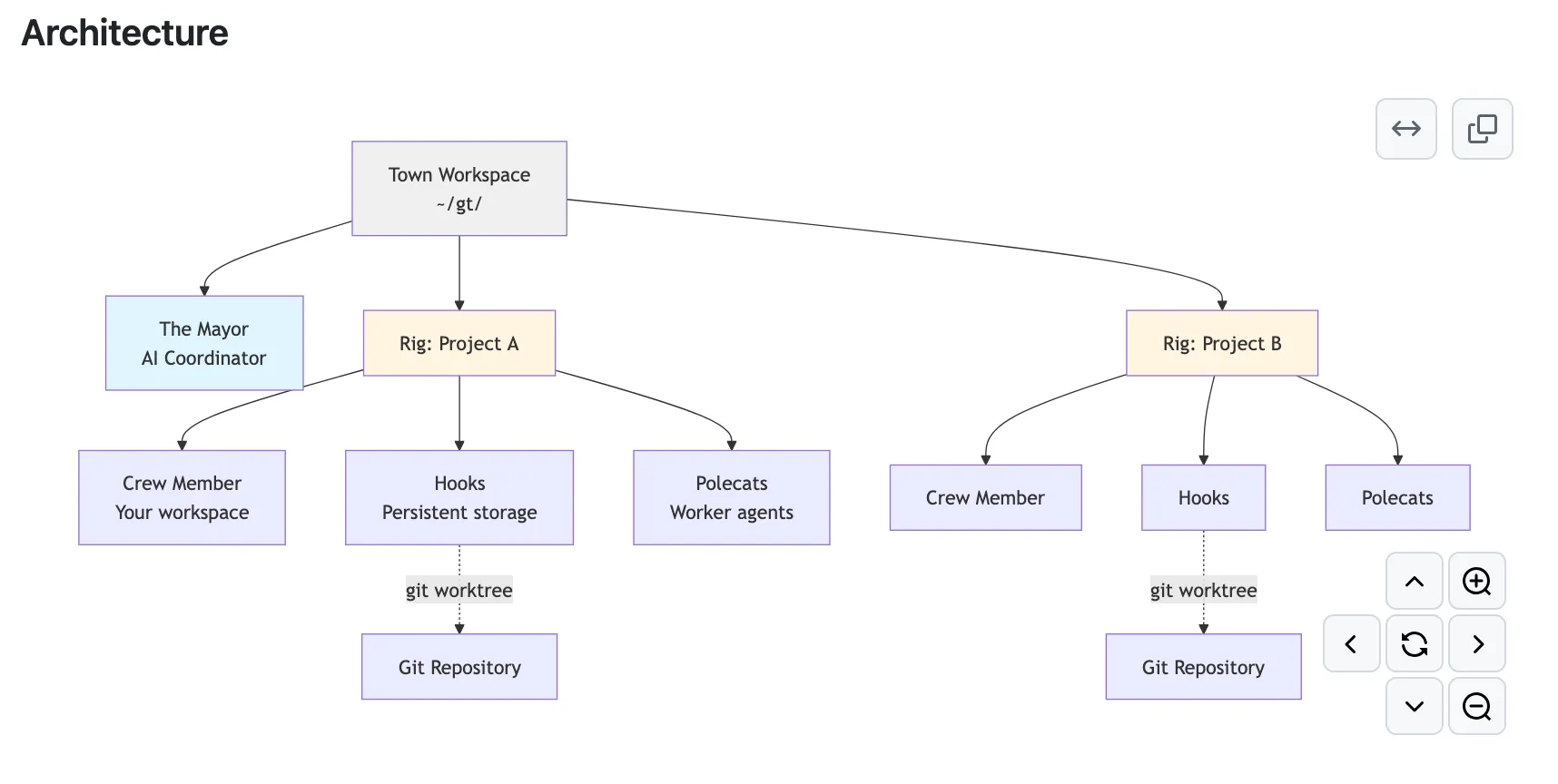

The Architecture

Single source of truth per skill:

skills/

treeos-release-version/

SKILL.md

run.shSKILL.mdis the canonical instruction file.run.shis the canonical script (short name, always in the same place).

Claude entry point (symlink):

.claude/commands/treeos-release-version.md -> ../../skills/treeos-release-version/SKILL.mdClaude still sees its command file, but it’s just a symlink to the real skill file. No duplication.

Codex entry point (symlink):

~/.codex/skills/treeos-release-version -> /path/to/repo/skills/treeos-release-versionCodex loads from its own central skills directory. So the solution is the same: symlink the skill folder.

Why This Works

- No drift. You only edit

skills/<name>/SKILL.md. - Both agents stay in sync. One file, two entry points.

- Short script names. Everything is

run.sh, which keeps paths readable. - Easy to audit. Every skill is a folder; you can scan it with your eyes.

A Few Tricks That Matter

1) Use SKILL.md as the canonical file.

Codex is strict about frontmatter. It expects name and description in YAML at the top. That’s your single most common failure mode.

2) Don’t duplicate scripts.

If you have scripts inside .claude/commands, they’ll drift. Move them into skills/<name>/run.sh and reference that in the instructions.

3) Claude supports symlinks.

You don’t need a generator script. Symlink the .md files and keep the content in one place.

4) Mac is case-insensitive.

You cannot have both skill.md and SKILL.md. Pick SKILL.md and stick with it.

Installing Skills for Codex

Codex only loads from its own directory, so you need to link your skills into it. I added a tiny helper:

./scripts/install-codex-skills.shIt walks through skills/* and symlinks each one into ~/.codex/skills.

That’s the only “install step” you need. Re-run it when you add a new skill.

The Result

- Claude sees the skills through

.claude/commandssymlinks. - Codex sees the same skills through

~/.codex/skillssymlinks. - You edit one file, everything stays consistent.

I’ve implemented this setup fully in the TreeOS repo — you can see the exact structure, symlinks, and helper script here: ontree-co/treeos.